Notes From A Lecture on the Birthday of Carolee Schneemann by Illia Razumeiko

The lecture was delivered by Illia Razumeiko and took place on October 12, 2024 – the birthday of Carolee Schneemann. On that day, her Foundation, in collaboration with the Stanford University Library, made publicly available over 3,700 pages of the artist’s diaries. To mark the occasion, we shared a cake, watched, and discussed several key works by Schneemann that have shaped the history of art over the past seventy years.

Carolee Schneemann was an American artist known for her multimedia works exploring the body, sexuality, gender, art history, the private, and the political. Initially emerging from the tradition of abstract expressionism, Schneemann worked across a wide range of media – from contemporary dance and theatre to video installations and performative lectures – always declaring: “I am an artist!”. .

Illia Razumeiko is a composer, co-founder of the contemporary opera laboratory Opera aperta in Ukraine, and a doctoral student in the Artistic Research Centre at the Vienna University for Music and Performing Arts.

Carolee Schneemann, an American artist of German descent, firmly identified herself as a painter and visual artist, despite working across a wide range of media, including performance, dance, and theatre. Her creative process always began with paintings, which later evolved and came to life in various forms.

Although Schneemann received the Golden Lion at the Venice Biennale in 2017, her work remains relatively unknown in Eastern Europe. She meticulously documented her practice, and her archive is still being expanded and reinterpreted. Some of her texts are now partially available online on the official website of the Carolee Schneemann Foundation.

Schneemann was born in 1939 in the United States and belonged to the generation of artists shaped by the aftermath of World War II. During her formative years, the German-American diaspora often rejected its own cultural identity. Working within a German cultural context was nearly impossible. As a result, Schneemann’s work contains no references to classic German texts like Faust or German philosophy. However, there is one notable exception: her pieces occasionally draw upon the music of Johann Sebastian Bach.

Music and the Avant-Garde

The context in which Carolee Schneemann developed as an artist was the multilayered American avant-garde scene centred in New York, particularly Manhattan. After World War II, the area became a hub for experimentation in various forms of art: painting, theatre, dance, and music.

Music held a special place in Schneemann’s practice. She listened to music while painting, and music was an essential part of her conceptual thinking. One of her favourite figures was Wanda Landowska – a Polish harpsichordist of Jewish descent who rose to prominence in France in the 1940s. Landowska revived the harpsichord as a concert instrument and was one of the few performers whose recordings sold in the millions. In the 1940s, fleeing the Nazis, she emigrated to New York, where she rebuilt her career from scratch. Schneemann listened to Landowska extensively and even included her photo in some of her collage works.

Schneemann’s first husband, James Tenney, with whom she lived for ten years, was a pioneering avant-garde composer and theorist. One of his most striking works was Postal Pieces: ten short compositions written for friends, each score printed on a postcard. Tenney’s music was highly conceptual. He was part of the American avant-garde scene, in which musicians posed fundamental questions: What is music? What is sound? What is a person who performs musical gestures? Artists were more interested in pure music, not tied to text, voice, or meaning, but rather in sound as a physical phenomenon.

Tenney collaborated with Schneemann on several projects: he composed music for her and took part in her musical and dance-theatre performances. For three years, he worked with her on the erotic-experimental film Fuses (1964–1967). Shot on 16mm film, the piece was hand-processed by Schneemann – she burned, scratched, cut, and exposed the footage to acid. One central figure in the film was Schneemann’s cat, Kitch. Schneemann even dedicated the array of works to her cat, and after the cat’s death, Schneemann created a large installation incorporating its mummified body.

Screenshot of Carolee Schneemann’s video work “Infinity Kisses” (2008)

Another important figure in the artist’s life was Cézanne. For Schneemann, the French post-impressionist was a kind of imagined woman artist, someone who had never existed. As a child, she came across a book about Paul Cézanne and mistakenly thought he was a woman named Anne (Cez-Anne). Schneemann dreamed of becoming a great woman artist whose works would be displayed in major museums. In 1975, she wrote her first significant book, Cézanne, She Was a Great Painter. From that “slip of the tongue,” from that early feminist “signal,” many of Schneemann’s works were born.

Abstract Expressionism and Collage

While studying fine arts at the University of Illinois, Schneemann’s work was often perceived as provocative and sparked controversy among her professors. She painted herself nude – an act of defiance against established norms. In 1940s-50s America, long before the sexual revolution and the rise of Playboy, society remained deeply conservative and clerical. Painting not a nude model, but one’s own naked body as seen in a mirror, was considered indecent. Most of Schneemann’s student work falls within the tradition of Abstract Expressionism, a movement that emerged in the United States after World War II, when the country became the epicentre of global art. One of its most renowned figures, Jackson Pollock, is closely associated with the concept of “performative painting.” Pollock painted in motion, and footage of his process gives the impression that he was dancing. Abstract Expressionism allowed for a fundamental shift in the perception of painting.

After graduating, Schneemann moved from painting to collage. Her 1960 work Tenebration is a semi-collage that features photographs of Wanda Landowska, Brahms, and Beethoven. One can read in this composition the artist’s desire to place two great male composers alongside a female musician, positioning them as equals within the same visual space. In the postwar period, collage as an artistic medium flourished in both Europe and America. Numerous variations emerged: expanded collage, performative collage, assemblage. At the same time, other art forms began to adopt collage as a method or lens. In this context, theatre and performance were often seen as large-scale collages—spaces where disparate elements drawn from the surrounding world come together into a unified artistic whole.

Carolee Schneemann, Tenebration (1960)

Selected Works

In 1963, Carolee Schneemann created the collage series Eye Body (1963), consisting of 36 photographs. In these images, the artist depicted her nude body within the space of her own studio. Schneemann conceived the photographs as works intended for museum display. At the time, museum collections were almost entirely composed of works by male artists. She sought to claim her place in art history on equal footing with men by presenting her own vision of female sexuality. Eye Body became a landmark work in the history of feminism.

American critics reacted to Eye Body in different ways. George Maciunas, founder of the 1960s avant-garde movement Fluxus, wrote a letter formally excluding Schneemann from Fluxus, citing her “overt eroticism, self-love, narcissism, and baroque tendencies” in the series. The artist later reflected on this moment as an attempt by men to suppress her right to speak through the language of her own body in art.

One of Schneemann’s most important performances was Noise Bodies (1965): a musical, performative, and visual composition. Together with her husband James Tenney, the two were adorned with various sound-making objects specifically designed for the piece, as well as a textual score.

Among Carolee Schneemann’s influential performative works is Meat Joy (1964). The premiere took place in Paris, and later the piece was performed in London and New York. It is a theatrical-performative, hour-long “orgy” featuring two women and two men. The piece includes a lot of meat, fish, dead chickens, and birds. The performance is post-erotic, celebrating corporeality. Since the action took place in public spaces where full nudity was not allowed at the time, the performers wore underwear. Fifty years later, Danish choreographer Mette Ingvartsen sought to recreate Meat Joy with its original participants. In 2014, she reached out to Schneemann with a proposal to restage the performance. Mette was interested in exploring why people undressed in the 1960s and what they were manifesting with their bodies. Schneemann replied to her letter with a request not to repeat the performance, as it was “time-specific”, belonging to a particular historical moment and remaining part of the 1960s.

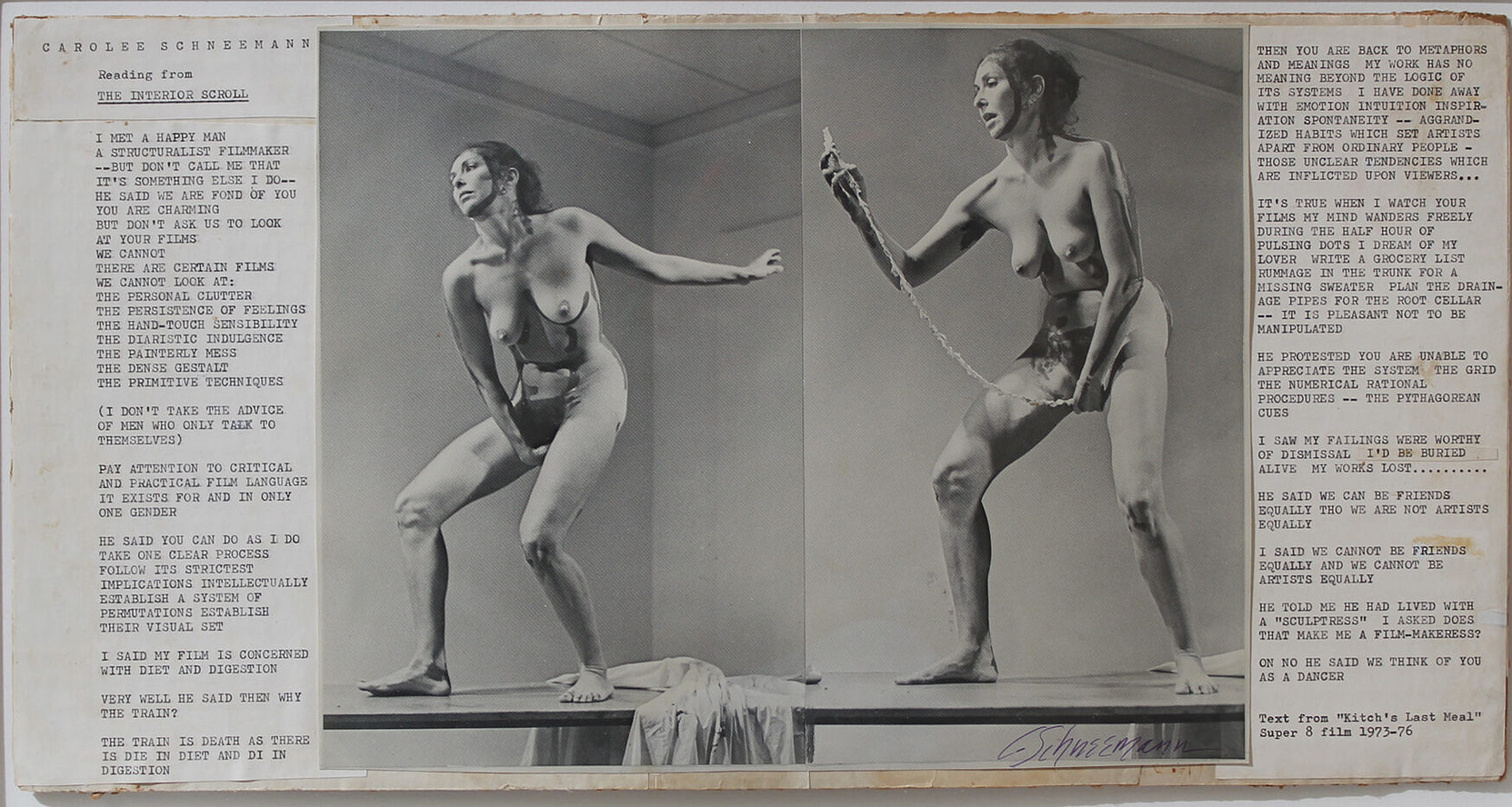

The culmination of feminist performative acts – and Schneemann’s most well-known work – is Interior Scroll (1975). The idea first emerged in early 1974 as a drawing, and later materialized into a live performance, which Schneemann also described as a form of drawing. In public, the artist pulled from her body a long text-poem, a kind of letter to a male director who had told her ten years earlier that she would never become a filmmaker. Interior Scroll became a classic of 20th-century performance art.

Carolee Schneemann, Interior Scroll (1975)

Also considered a classic is the performance-installation dedicated to Jackson Pollock – Up to and Including Her Limits. Documentation of the work and fragments of the canvases from the performance are now held in several contemporary art museums. It marks the culmination of understanding abstract expressionism not simply as painting, but as a fusion of painting and performance. For Schneemann, this was a multi-year process: at home and outdoors she painted while tying herself to a tree, for which she developed an entire system of rigging. She explored the physicality of the artist, particularly seeking to imagine herself entirely as a paintbrush.

Political Art

A landmark year for politicized American performance art was 1968, a year marked by the protests in France, the entry of Soviet tanks into Prague, and the culmination of the Vietnam War. The targets of criticism for artists were many, from capitalism to armed conflicts. Carolee Schneemann dedicated several performances to the Vietnam War. She worked with photographs arriving from the front lines: based on these, she created various works. One example is the immersive performance Snows (1967), which was triggered by a photograph of Vietnamese children commuting to school through trenches, hiding from bombings. The artist invited an audience in Manhattan to step into the role of those children. She built a complex structure and deliberately frightened people with strobe lighting, aiming to make them feel the horror of the Vietnam War.

One of her later works is Plague Column (1995). This feminist video installation combined the female figure of “plague” from a Baroque column in Vienna with footage of a real woman who had breast cancer. Schneemann dedicated the installation to a new interpretation of the image of the witch. She referenced the ancient, medieval, and Baroque notion of the witch as the source of all misfortunes—someone to be burned so that order could be restored in the city. The artist’s later works often engage with the history of art and its rethinking.

Terminal Velocity (2001–2005) is a series of photo collages by Schneemann dedicated to the tragedy of September 11, 2001. That day, terrorist planes crashed into the Twin Towers in the middle of Manhattan, near the very streets where the avant-garde of the 1960s and ’70s once thrived. This attack marked the end of the 20th century and the beginning of the 21st, an era defined by the so-called “war on terror.” Schneemann created collages using photographs of people who had been inside the Twin Towers and jumped from the upper floors in an attempt to escape the fire. The term “terminal” velocity refers to the speed of free fall.

Carolee Schneemann’s body of work spans a wide range of media: films, semi-musical compositions, performances, paintings, and collages. But at times, it seems that the most interesting are her texts that truly deserve to be read.

The translation of this material was made possible through the Per Forma grant program, implemented by the Kyiv Contemporary Music Days platform with the support of the Performing Arts Fund NL and the Ministry of Education, Culture and Science of the Netherlands, aimed at developing the performing arts sector in Ukraine.

Translation by Yurii Popovych