Museum as a Performative Act. Notes From A Lecture by Illia Razumeiko

On December 24, 2022, Illia Razumeiko delivered a lecture titled The Museum as a Performative Act. The lecture took place at the Khanenko Museum during the first round of the Fellowship. In his talk, the author questions the contemporary misinterpretation of the term “museum.” Illia shares his perspective through the lens of museology, performance, and theatre theory. In the fall of 2022, Illia Razumeiko and Roman Hryhoriv presented Genesis. Opera of Memory at the Khanenko Museum.

Illia Razumeiko is a composer, co-founder of the contemporary opera laboratory Opera aperta in Ukraine, and a doctoral student in the Artistic Research Centre at the Vienna University for Music and Performing Arts.

Museums and performance were once inherently intertwined, though they are rarely viewed together today. The museum as a space has radically transformed its meaning since the days of Ancient Greece. Each era in European culture has redefined and often distorted the museum’s “original” etymological idea.

The Mouseion

Etymologically, “mouseion” means “the temple of the Muses.” In Theogony (an Ancient Greek poem about the origin and genealogy of the Greek gods), Hesiod writes that there are nine Muses, daughters of Mnemosyne, the goddess of memory, each responsible for a different branch of the arts. Among the arts overseen by the ancient Greek Muses, there is nothing that resembles what is now typically exhibited in a Western European-style museum of the modern era or even of several past centuries since the Renaissance.

In Hesiod’s time, the Muses were responsible for performative arts. Poetry and theatre – foundations of ancient Greek culture – existed in the form of folklore. Seven of the nine Muses were in charge of what we now broadly define as performative arts: dance (Terpsichore), pantomime and hymns (Polyhymnia), erotic poetry (Erato), lyrical poetry (Euterpe), epic poetry (Calliope), comedy (Thalia), and tragedy (Melpomene). The remaining two, Clio and Urania, represented history and astronomy. So, the visual arts, which now make up a large portion of what we call a museum, were only a small part of its original scope. Renaissance and Enlightenment scholars and thinkers made a fundamental “mistake” in their interpretation of Greek texts: they read them through the lens of their own time’s categories and tools. As a result, the very concept of the museum and theatre came to acquire a different meaning, one far removed from its original.

This “distorted interpretation” was addressed by Norwegian composer Trond Reinholdtsen, who sought a different path in his work. In the 2010s, he staged the opera Orpheus and Eurydice in his apartment. His premise was that Italian composers like Monteverdi and his contemporaries had completely misunderstood what ancient Greek theatre was and what “opera” could be; that’s why we inherited an overwhelmingly anti-performative and anti-theatrical structure in the form of Western European musical opera. Reinholdtsen believed we need to start the story anew, to reimagine the myth of Orpheus from the beginning. His Orpheus and Eurydice is a multidisciplinary work in which performance is aligned with a strategy to dismantle established understandings of opera. In fact, Reinholdtsen created a new opera in which he served as composer, director, and often even performer.

Screenshot from the recording of Orpheus and Eurydice opera by Trond Reinholdtsen

Museums, Opera, and Colonialism

To understand the “distorted interpretation” of the concepts of museum, performance, theatre, and opera, we can turn to a single ancient Greek myth. In this myth, the god Apollo takes the Muses from Mount Parnassus to the Temple of Delphi. At Delphi, a key part of Apollo’s great sanctuary was the theatre. The entire complex – site of the Pythian Games – was essentially a festival of performance in the 5th-4th centuries B.C. The Pythian Games included theatre in all its forms, including competitions among poets and playwrights, as well as sporting events.

The concept of the museum as a building, i.e., the Mouseion, emerged later during the Hellenistic period, when Greek democratic city-states and autocratic city-states began conquering neighbouring territories. As part of this colonial expansion, the first building referred to as a museum or Mouseion was established in Alexandria, in the north of modern-day Egypt. Following the classical layout of a Greek city, this structure was located near the theatre and the Library of Alexandria. However, it was not a museum in the Western European sense of the word, it was more of an academy, where representatives of the Hellenistic world taught and studied. Still, even at that early stage, the Greek museum bore the same flaws now attributed to Western European museums. The Mouseion in Alexandria was a direct result of colonialism: it was part of a conquering war that brought Greece to Egypt.

When Alexandria was founded by the Macedonians, the museum was created to reinforce the dominance of Hellenistic culture. It served as a tool of propaganda, a vehicle of imperialism, and a means of controlling the local Egyptian and Jewish populations. Thus, the first museum arose during a time when Greek civilization was nearing its end and would soon be overtaken by Rome. When history approaches its end, the museum emerges as a means of recording and preserving that history.

Museum Spaces

The classical form of the museum is modelled after the Parthenon with its row of columns. Iconic examples of such architecture include the British Museum, the Austrian Parliament, and the Zaporizhzhia Music and Drama Theatre. However, what takes place inside these buildings does not reflect the original meaning of the term “museum.” These examples are rooted in a 17th-century vision, when classical opera, theatre, and the modern concept of the museum as we know it first emerged.

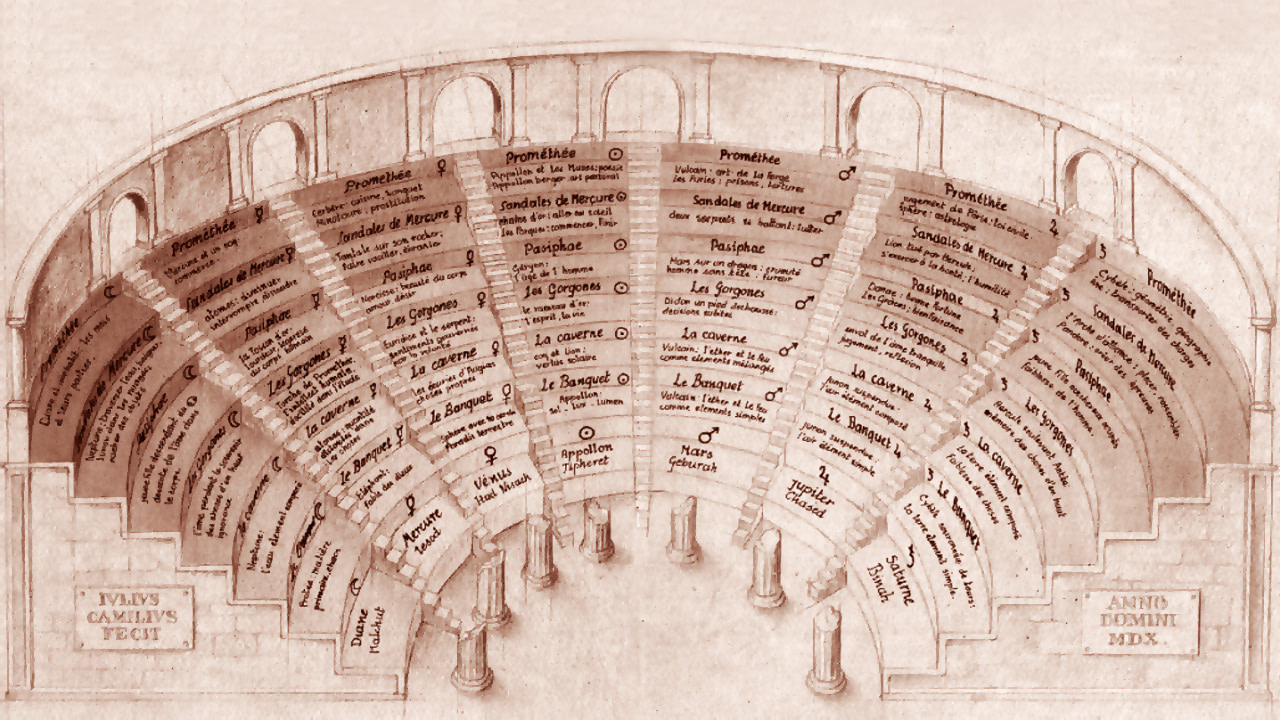

Yet, Western cultural history also contains spatial concepts that move in the opposite direction. One such example is the utopian idea of the Theatre of Memory by Giulio Camillo, developed in the 1540s. This was a mnemonic installation described in a book, never fully realized, or perhaps only built as a model that has not survived. Camillo envisioned the Theatre of Memory as a grand hall designed in the style of an ancient Greek or Roman theatre, but with a crucial twist: the spectator stands on the stage. The amphitheatre that the viewer observes is, in fact, the Library of Babylon. According to Camillo’s concept, this library contains all the texts of humanity: Greek, Roman, alchemical writings, visual imagery, and more.

Drawing by Giulio Camillo of his Theatre of Memory

Camillo’s Theatre of Memory stands as an exception to the rule, because the Renaissance project of reviving ancient Greek models ultimately failed in many respects. Instead, opera and the museum have remained inseparably linked ever since the birth of opera in the 17th century. By the 19th century, this relationship became especially pronounced. Richard Wagner’s theatre in Bayreuth and the Palais Garnier in Paris both, built in the 1870s, represented two antagonistic aesthetic visions. Bayreuth, devoted exclusively to Wagner’s works, could be considered the first cinema due to its groundbreaking auditorium that combined the structure of a Greek amphitheatre with a minimalist space devoid of boxes and lavish decor. Garnier, often referred to as the last Baroque theatre, functioned more like a museum: a site for the reconstruction of opera’s “golden age,” where the building’s architecture, adorned with muses on its façade and throughout its interior, turned it into a kind of extramuseum.

Opera is, in many ways, a museum intrinsically tied to colonialism. Take, for instance, Giuseppe Verdi’s Aida (1879). Its creation coincided with the widespread euphoria around Egyptology, during which European museums scrambled to drag monumental “stones” out of Egypt and open Egyptian art departments. Aida was commissioned for the inauguration of an opera house in Cairo, at a time when Egypt was under French occupation. Verdi attempted to reconstruct Egyptian music, though it was nearly impossible to recreate in the way it actually sounded. Aida is a costumed reconstruction of an era and a symbol of the archetypal Western colonial museum.

The Museification of Performance

In the context of alternative perspectives on the museum, the figure of Belgian artist Marcel Broodthaers is particularly interesting. Until the age of 40, he was a poet. Later, in Brussels, he decided to take up contemporary art and began selling it. He was one of the first to work in the genre now known as institutional critique. In his studio, he created a large installation titled Museum of Modern Art. Department of Eagles. The installation consisted of traditional interwar French avant-garde aesthetics but also featured an exhibition of artifacts related to eagles. This “museum” existed as an installation for four years, after which the artist declared it bankrupt and announced its sale.

Another way to imagine the museum is the Iron Curtain in Vienna. In 1881, the Viennese theatre – then seating 1,800 people – burned down, killing 600 individuals. As a result, fire safety regulations were changed. The Vienna State Opera began using an iron curtain to separate the auditorium from the stage area. Before World War II, this curtain featured a painting of Orpheus and Eurydice, which was later destroyed by an aerial bomb. Since 1998, the 170-square-meter curtain has been transformed into a museum space. Each new season, it features a work by a contemporary artist, which audiences observe before the performance. The project is fascinating in that, on the one hand, it is experimental and exploratory, and on the other, distinctly “Viennese” and bourgeois. It brings together the museum and opera in a single physical location.

Cy Twombly’s work Bacchus at the Iron Curtain in Vienna State Opera House, 2010-2011

In Vienna, the fusion of museum and performance is also tied to Viennese Actionism, particularly the figure of Günter Brus. He began staging public actions in the 1960s, which gradually became more radical. During his Viennese Walk (1965), Brus was supposed to walk from the museum to the opera. However, near the Albertina, one of the city’s largest art and contemporary museums, he was detained by Austrian police and taken into custody. Brus’s performances were seen as deviant by contemporary Viennese society. The most infamous Actionist event took place at the University of Vienna, where members of the group simultaneously urinated, engaged in political propaganda, and sang the Austrian national anthem. Today, a museum in Brussels is dedicated to Brus, documenting and studying his work. It is designed in the typical “tapestry-style” layout of a 16th-century Dutch gallery: an attempt of performance art museification.

Another Austrian, Hermann Nitsch, followed a similar path: from ultra-radical performances to establishing his own museum. Although he did not directly work with Antonin Artaud’s texts, and even claimed he was initially unaware of them, their aesthetics often overlapped on a formal level. In the 1960s, Nitsch began with provocative performances in small Viennese galleries, involving blood, dismembered cows, and similar elements. Over time, these evolved into his grand theatrical concept: the Theatre of Orgies and Mysteries. In a castle he purchased in 1971, Nitsch staged a six-day mass that fused the spirit of ancient Greek theatre with various Christian rituals. Two decades later, he returned to painting. His extreme experimental performance art ultimately transitioned into the commercial sphere. The legacy of his actions became monumental canvases that could be purchased and displayed in banks or offices. In the end, his radical performances were transformed into commercial, bourgeois art: something fit for a museum or the private collection of a wealthy patron.

Another example of this museification of performance is Marina Abramović. She followed the trajectory from performance art to opera. Abramović began her artistic practice at a time when the dominant discourse treated theatre and performance as antagonistic. Many early critics and scholars believed that performance was something alive – an event unfolding in the here and now – while theatre was dead, overly rehearsed, and staged. Yet everything Abramović had advocated for in the 1970s ultimately culminated in a staged, artificial, and melodramatic opera production: her 2019 work Seven Deaths of Maria Callas. I see this production as the death of performance itself. One could even call it the Aida of the 21st century.

In sum, what unfolded throughout the 20th century was, on the one hand, the performativization of the museum, and on the other, the museification of performance. In the long arc of history, museification always prevails, just as death triumphs over life. Still, I believe it remains valuable to pause from time to time and reflect on the theories of the museum, performance, and theatre: wandering the intricate labyrinths that connect them.

The translation of this material was made possible through the Per Forma grant program, implemented by the Kyiv Contemporary Music Days platform with the support of the Performing Arts Fund NL and the Ministry of Education, Culture and Science of the Netherlands, aimed at developing the performing arts sector in Ukraine.

Text based on a workshop audio recording by Hanna Shchokan

Translation by Yurii Popovych