Hanna Vinohradova about autoethnography and performance “Me and Olha”

In 2023, as part of the Southern Edition of the Antonin Artaud Fellowship, Hanna Vinohradova conducted a workshop. At that time, she was working on the work in progress project “Me and Olha” and later became part of the mentoring team supporting projects focused on the southern regions. In this notes, Hanna shares insights into the creation of “Me and Olha”, the relationship between mother and daughter, the impact of growing up in the 1990s on her artistic practice, and the local culture of Donetsk.

Hanna Vinohradova is a performer and choreographer. She was born and raised in Donetsk and moved to Kyiv in 2014. She leads workshops in performative practices and contemporary dance. She creates solo performances as well as collaborative works with fellow artists. Her artistic practice often draws on an autoethnographic approach. She is a co-founder and teacher at the children’s dance school “Cheloveki.” She is also a member of the TanzLaboratorium research-oriented group.

With the project “Me and Olha”, which was conceived as a work in progress, I applied for the Antonin Artaud Fellowship. In the title, “me” refers to me – Hanna Vinohradova – and Olha is my mother. We have several points of connection: we share a studio called “Nide ne tysne” (“Nowhere Pinches”), where my mother sews and I do the rest. But the main thing is that my mother used to be a ballerina, and I also work with the medium of dance.

A few years ago, even before the COVID era, I had the idea to bring my mother into a studio or dance space and try moving together. It sounds simple, but in reality, it was anything but difficult, as my mother is now 65, and the workshop project wasn’t originally meant to involve any kind of joint dancing. What made things even more complicated was the fact that we’d never really been close: not in that best-friends kind of way. Still, as I slowly “sneaked up” on her with the idea, I began to see that our shared movement held a lot of potential. Eventually, I told her, “Mum, if you want the dresses to sell, let’s go dance.” I rented a studio, and we filmed some footage. I edited four different videos and posted them on the studio’s page. It turned into a mini-series we called “Dances and Dresses”. Later, I realized there was something deeper there and thought that one day I’d like to develop this story with my mum further, to make it more theatrical, because it clearly had something compelling.

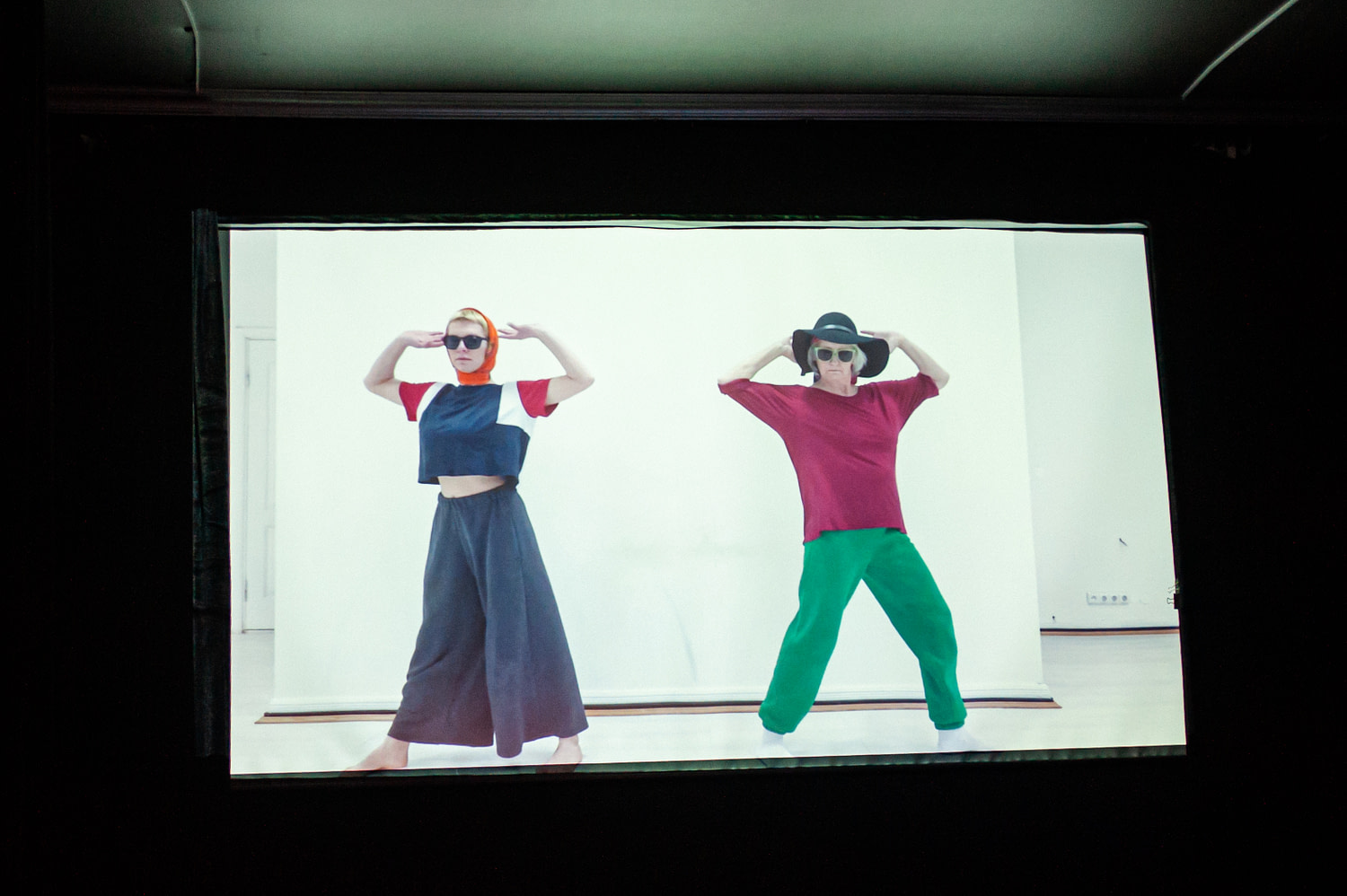

Hanna Vinohradova, performance Me and Olha. Photo by Valeriia Landar, 2022

A few years later, I was selected for the Antonin Artaud Fellowship. But my mum declared she wouldn’t take part. The conflict was that throughout her youth, she had been a ballerina – appearing onstage, elegant and poised in gorgeous costumes – and now here I was, asking her to do something radically different: to be onstage and not dance. On top of that, she said she was “too old for this” and pointed out that she was going grey; she now has a rule not to dye her hair until the war is over. I didn’t want to impose “European ideas” on her or argue: I know how forceful and didactic that can feel. You can’t force someone to accept an idea when they’ve lived their whole life thinking differently. But I had a purely selfish goal: to convince my mother to appear on stage. So we started negotiating. In the end, she agreed to appear on video, but not live on stage.

At first, my idea for the project was to enter into a dialogue with my mother, to create an encounter between two choreographers and performers with very different backgrounds. She had been a ballerina and later taught children; she raised many talented dancers. There’s still something very classical-ballerina about her, and yet at the same time, she resists the pressures placed on the body: she loves feeling free, is always looking for comfortable furniture, wand ears oversized clothes. I proposed that she engage in a dialogue with my style of dance, as her student, now creating performative art. I had no concrete plan, I just wanted to see what would happen.

Hanna Vinohradova, performance Me and Olha. Photo by Valeriia Landar, 2022

No matter what I started working on, I always ended up in Donetsk. That’s where we lived – so that’s where I, my mother, and our dances are rooted. I became interested in my culture, layered and specific to us. After her time at the Donetsk Opera and Ballet Theatre, my mother began working as a choreographer at the Youth Palace “Yunist”. Later, I worked there too. It’s your typical Soviet-style Palace of Culture. My mother choreographed there for many years, and I, as a child, would sit in the audience and watch.

While working on “Me and Olha”, I revisited old archival footage. For a long time, I felt resistance inside — a sense of distance and rejection: all those variety dances felt outdated, unfashionable, not mine. I thought I choreographed “real” dances, I do performance art. But the truth is, I grew up with those dances. That’s what sparked the need to unpack it all, to spend time with my past. I watched videos from the 1990s and began to see those dances differently. They struck me in a new way – suddenly they felt powerful, even cool – precisely as a cultural layer. They gave a sense of what was actually happening at the Youth Palace in Donetsk, and of the kinds of performances my mother was staging back then.

One of the dances dates back to the early 1990s. A group of girls in Eastern-style costumes danced to “It’s My Life” by Dr. Alban. My mother sewed the tops and Eastern skirts herself. The choreography was built as a mix of movements from Eastern dance, ballet battements, pirouettes, and jumps. While watching the recording, I imagined Donetsk in the 1990s — with the Youth Palace standing next to the stadium where miners watched the matches. I clearly remember how I felt as a child watching that dance: I thought the girls on stage were fairies and that I would never be able to dance so “magically.” I asked my mother how the idea to stage it came about in the 1990s. She told me no one actually spoke English, but they knew the phrase “It’s my life.” “We understood it meant ‘this is my life,’ and for me, life was dance,” she said. They chose the Eastern-style costumes because that was trendy at the time. Cassettes of foreign performers were popular. My mum says that just “kicked in”.

Hanna Vinohradova, performance Me and Olha. Photo by Valeriia Landar, 2022

I learned the movements and choreography from video recordings. I even found a similar costume on OLX. Working with this material turned out to be difficult: I realized that my childhood impressions were one thing, but being with this dance now, embodying it was something super strange and deeply performative. I consulted with my mum; she started giving me corrections, but I felt like I just couldn’t “place” my body into it. For a performer, when things don’t come easily, when there’s discomfort or pressure — that can actually be very fruitful. And that’s exactly what this dance has remained for me: it never became comfortable; the distance stayed, but now I feel it really gives me a rush. After that, I rewatched many of my mother’s dances: some of them I absolutely loved: they were technically complex and very well prepared.

There was another dance I tried to reconstruct without video – it had never been filmed. My mum choreographed what she called “mannequins,” where the girls danced to Kiss by Tom Jones and The Art of Noise. I still remember the childhood impression: they looked so cool: in sunglasses and scarves. For Donetsk in the 1990s, it was all just wow. That’s how the dream was born: to recreate that dance live with my mum, relying on what she remembered. I pulled her into the studio, and we rehearsed together, recalling the moves. Thirty years had passed, but she still remembered the choreography she had once created. We recreated a fragment of that dance and filmed it. Now I’m completely in awe, this is what I grew up on; it feels like I’m made of these dances my mum used to choreograph. She also explored Indian dance: took workshops from a woman who had married an Indian man. So there was an Eastern influence woven into her choreography as well.

Mentions of the “Yunist” Palace take me back to Donetsk: I often find myself walking its streets in my mind, catching familiar smells. It just appears, even during rehearsals, it comes to me. And at some point, I began exploring the theme of terykons (spoil tip in Ukrainian). During the work-in-progress discussions, I realized that the topic resonated with the audience. In Donetsk region, there are around 600 terykons: artificial hills formed from mining waste, constantly smouldering: they are “alive,” warm. Terykons have an “inner life” similar to volcanoes, which makes building near them dangerous, though these safety regulations were often ignored during Soviet times. We, as kids, were told not to walk on the terykons – there might be hollow spaces inside, and there was a real risk of falling through. But no one listened.

For me, terykons are a kind of cultural layer. Donetsk, in a way, has appropriated them. People organized music festivals and motocross races there; a Kyiv-based artist even painted a carpet pattern on one of them. It’s a cultural theme for the people of the East themselves: you can go for a walk on the terykons, ride around, they’re, in general, something “of our own.” At the same time, they’re also something dangerous, something that keeps smouldering.

Hanna Vinohradova, performance Me and Olha. Photo by Valeriia Landar, 2022

In this project, I didn’t directly address the theme of the full-scale invasion. But the feeling of that dangerous, smouldering place we had lived near for so many years was always associated with war. I even choreographed a dance built on that image. For years, when I came to Kyiv after 2014, I felt ashamed to “show” my passport somewhere. Back then, being “from Donetsk” was humiliating: it meant being denied a rental apartment, facing difficulties getting a job. Everyone asked about your registration.

Now — I am from Donetsk! Since the full-scale invasion, that identity no longer feels like a burden; many people now come from different cities, it’s perceived differently. I feel the need to say that I come from this kind of culture, that my mother danced like this, my terykons are like this: I don’t fully know them, I’m afraid of them, but they are mine.

I could now register officially in Kyiv, but I haven’t done it. During a work-in-progress presentation, Larysa Venediktova asked me what my intention was. I hadn’t thought about it before, but I said I want to reclaim Donetsk. In other words, “Me and Olha” isn’t just about my relationship with my mother – it’s about something broader. I’m not sure I would be so interested if there hadn’t been this distance, this rupture. Since 2014, I’ve been dreaming about Donetsk. I dream of walking my favourite route: from Shakhtarska Square down Artema Street all the way to the Central Department Store.

I’m not sure we’ll get Donetsk back in the way some proclamations in numerous statements suggest. It’s a disjointed conflict over occupied territory. In this project, I’m more focused on finding my own story, my own culture. I say that my culture is this dance, these terykons.

Lately, I’ve been reading books about the East of Ukraine. For example, The Rise of Ukraine’s Sun – a rather factual work in which the author describes Donetsk and Luhansk from the perspective of what was and still is Ukrainian there. It makes me wonder how I could have grown up without encountering the things she writes about. I studied Ukrainian at school only until the 8th grade, it wasn’t even a mandatory subject. After that, we had Russian language, Russian and world literature. My culture isn’t rooted in Taras Shevchenko, although I did memorize I Was Thirteen (as translated by John Weir) at school: my culture is in those dances of the Donetsk Youth Palace. I feel it, I can reflect on it; I’m curious to explore what is truly mine and how I can speak about it.

The translation of this material was made possible through the Per Forma grant program, implemented by the Kyiv Contemporary Music Days platform with the support of the Performing Arts Fund NL and the Ministry of Education, Culture and Science of the Netherlands, aimed at developing the performing arts sector in Ukraine.

Text based on a workshop audio recording by Hanna Shchokan

Translation by Yurii Popovych