Footprints of Places. Asia Pavlenko on the Performances of Nana Biakova and Maryna Shchehelska

In August 2024, Maryna Shchehelska presented her work in progress Lost Sound of a Forgotten Place in Kyiv. She performed a carol that had been recorded in 2007 in the village of Yehorivka, Volnovakha district, Donetsk region. Later in November, Lost Movement, a piece created and first shown by Nana Biakova in Mykolaiv in 2023, was presented in Kyiv for the first time.

In this essay, Asia Pavlenko writes about the kinship between these two different works, created at different times and in different spaces.

Asia Pavlenko is a cultural researcher and author of affectionate texts on culture. She explores performance art, trauma, knowledge production, and everything in between.

Their titles echo one another. At their most basic, the Ukrainian words ‘втрачений’ and ‘загублений’ are rendered in English as the same word, lost. Something that cannot be recovered. Lost, as in ‘killed’, or dropped, abandoned by the roadside. Lost, like a ‘signal’, in the aftermath of something terrible. In the end, they are interchangeable.

Both performances are grounded in real places. Nana Biakova returns to Mykolaiv, where she was born and raised. Maryna Shchehelska sings the carol Oh, Wonderful Newborn Child, collected in the now temporarily occupied village of Yehorivka in Donetsk region. In doing so, they resemble archaeologists. Their tools — their bodies — are directed in different ways. Nana Biakova turns to a vulnerable anthropology: she observes herself, disassembles familiar landscapes and objects, and reanimates their testimonies. The paths of Maryna Shchehelska and the carol from Yehorivka cross almost accidentally, through a recording she found online. With no personal connections to the place, the artist establishes a relation to the Other through love: she builds the performance around this specific carol because it spoke to her (in daily life, Maryna is part of Drib, a women’s traditional music ensemble).

Maryna Shchehelska, performance Lost Sound of the Forgotten Place. Photo by Anastasiia Telikova, 2024

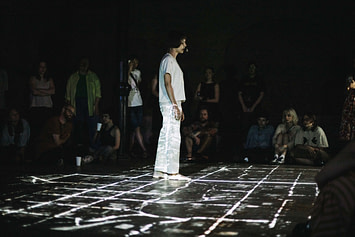

Nana Biakova, performance Lost Movement. Photo by Anastasiia Telikova, 2024

Ultimately, both artists move through the places they have pledged to witness. Nana Biakova, like a ghost, moves through the rooms and corridors of the Khanenko Museum, where the performance takes place. Maryna Shchehelska, reenacting the route of carolers visiting homes, follows a projection — lines traced over a satellite image of the village.

In the text Archaeological Tropes That Perpetuate Colonialism, two archaeologists from Indigenous communities in the U.S. Southwest reflect on the idea of ‘abandonment’ of the land. When Pueblo left previously inhabited areas, colonizers — white settlers — interpreted them as consciously forsaken and claimed them. Simultaneously, archaeologists took up their tools and marked the territory as past: now the land could be excavated, the artifacts extracted for research or museum display, the years flattened into a neat linear chronology. For Indigenous communities, however, movement and journeying between places are a vital part of culture, and these ‘abandoned’ lands remain cultural heritage, preserved in oral narratives and physical household items.

Although the artists’ personal geographies bypass North America, I connect them to the Pueblo on a different principle — centering on movement and place. Lost Movement, as an experience of returning to an ‘abandoned’ place, resonates with the mythology of movement in Indigenous communities, while Lost Sound of a Forgotten Place examines the abandonment of a temporarily occupied village.

I watch Nana Biakova enter the space: tense muscles, slow steps, complete control over each motion. A heavy brown leather jacket hangs from her head, its raised sleeves resembling antennas or rabbit ears. Screens on the walls flicker with waves. The videos, filmed by the artist in Mykolaiv, are mostly composed of water, just like the human body. Over 45 minutes, Nana Biakova slowly moves through three rooms and a corridor. In each space, she encounters dresses, sunglasses or earrings, as well as fragments of videos. A shared wave of time fosters understanding; the audience finds themselves alone with Nana Biakova, her objects, and Mykolaiv. The world beyond the museum walls moves separately and seems less urgent. And yet, great changes unfold outside: dust slowly settles in the artist’s Mykolaiv apartment, the cruiser Ukraina rusts, and empires crumble.

In the prologue to one of his books, Simon J. Ortiz describes a Pueblo person and their ritual. They take stock of all that matters: home, language, and selfhood. Then they set off on a journey, encountering diverse experiences, human and nonhuman beings. Whatever the emotions along the way, the Pueblo people keep moving. Despite danger, they return to themselves only after they have learned all they need to know.

“His travelling is a prayer as well, and he must keep on.”

According to Pueblo mythology, their ancestors emerged from the underworld in search of a new place, a home awaiting them. This long journey scattered people across the land. Those who could go no further stepped off the path and lived out their lives in settlements created along the way. The footprints of places where Pueblo people stayed bear witness to a long journey. They encourage descendants to return in acts of respect and connection with the past. Such sites include architecture as well as individual items, like fragments of pottery. In times when pilgrimages are not undertaken, places are kept alive through prayers, memories, and domestic storytelling.

Nana Biakova, performance Lost Movement. Photo by Anastasiia Telikova, 2024

In Lost Movement, Nana Biakova weaves together the heritage of two geographies central to her — Japan and Ukraine. Her bodily experience of Butoh, gained in exile, allows her to reinterpret the relics of her Mykolaiv life.

According to this philosophy of movement, she returns to herself after a journey. The objects in the performance — in the videos and in the museum halls — are footprints: impressions left both on Biakova’s body and in the places her path has crossed. One of these traces is fading in the port of Mykolaiv — the missile cruiser Ukraina. It connects to Mykolaiv’s recent past, when shipbuilding was its core industry. With the thought of a now-halted shipyard, the unfinished cruiser looms as a part of a former settlement. In footage from the Museum of Shipbuilding and Fleet, Nana Biakova documents gestures and sounds that also belong to this memory. At one moment, she rotates her wrists like a propeller.

Nana Biakova, performance Lost Movement. Photo by Anastasiia Telikova, 2024

Some objects come from the artist’s personal archive, for example, the dresses hanging on a clothing rack. From a conventional perspective, she wears them wrong: stretched over her head, layering styles and prints that supposedly don’t go together. Her raised arms become a torso; her chest becomes the hips. The dress seems to obscure Nana Biakova: covering her eyes, it becomes a body of its own. Leopard, pink, and silver — these prints and materials belonged to the artist’s mother, from which she sewed dresses of her own design. For international presentations, the costumes are packed in a suitcase like irreplaceable relics. As voices of a previous generation, they encourage a return — either as pilgrimage to reclaim them or as companions on a journey forward.

Pueblo movement is possible thanks, in part, to nature. Clouds, water, birds, and other nonhuman agents chart paths for the traveler. People orient themselves accordingly and also take responsibility for co-existing with the nonhuman. As Nana Biakova explains, in Butoh, “there is respect for objects as inhabitants of a secret world. […] to dance Butoh, you must explore what is not human, and become an object.”

My attention lingers on the glasses in one video. Sitting in front of a cabinet of glassware, the artist brings the glasses close and taps them together. Nearby are bundled bags and other packed belongings. The dusty Mykolaiv apartment is mostly empty and silent. No one uses it as a permanent home. When the crystal rings, what does it say to Nana Biakova? What trajectory does it sketch for her?

Among the glasses, the dresses, and the ships, this search will find no final answer. It will only offer scattered findings and experiences that will stay with the person on their journey, wherever they go. As long as life endures, so will motion.

If I imagine a feather duster in Nana Biakova’s hand, I draw a small spade for Maryna Shchehelska: the carol from Yehorivka is an artifact unearthed by her. During the performance, the artist sings it twice — one voice is recorded for later playback. In this way, she imitates the polyphonic tradition in which this carol is customarily sung. As she sings, Maryna Shchehelska moves along the satellite image of the village.

Public information about Yehorivka ends with its occupation in March 2022. In November 2024, Vilne Radio included it in a list of temporarily occupied settlements. It’s unknown how many people remain in the village, under what conditions they live, or whether the land is still habitable. So the artist and the audience both approach the place as lost. At the same time, we can only speculate about the fate of Yehorivka’s people and their carol. In fact, Maryna Shchehelska has no direct ties to the village’s past or present. Her first encounter with the place happens remotely, through online archives.

The movement is interrupted. The path between Kyiv and Yehorivka remains barely trodden. What does Kyiv mean to the people of Yehorivka, and Yehorivka, to the people of Kyiv?

Maryna Shchehelska, performance Lost Sound of the Forgotten Place. Photo by Anastasiia Telikova, 2024

Lost Sound of a Forgotten Place limits its own movement by the very language it employs. To cement such descriptions in a title, one should be certain that the sound is truly lost and the place indeed forgotten. But can one forget something neither the artist nor the audience knew before the performance or the work on it began? Drawing on DeepState maps, a satellite image, and fragments from the news, the artist marks the place as abandoned — with archaeological precision and detachment. Now it can be seeded, turned into material for an artistic work. The artist’s antitheses migrate from one description of the performance to another: a winter ritual held in summer; polyphony sung by a single voice; the joyful news of caroling interwoven with loss and sorrow. Within such a strict framework, I’m reminded of archaeologists staking out the perimeter of a dig site. The performance space unfolds strictly within these bounds, and nowhere else.

The exact perimeter reached by the shovel narrows and stiffens. As a viewer, I sit in this pit with my legs tucked in, unable to turn around. The carol, like a shard of a pot or tile, rests on an imaginary museum pedestal with a brief caption. I’m referring to it with a question. I turn to the exhibit on the pedestal, and it echoes back:

“I bear witness to something, to someone in Donetsk region. There is nowhere for me to make pilgrimages to, so I keep circling the same few meters. A winter ritual held in summer; polyphony sung by a single voice; the joyful news of caroling interwoven with loss and sorrow.”

Maryna Shchehelska, performance Lost Sound of the Forgotten Place. Photo by Anastasiia Telikova, 2024

I return with nothing.

Later, in a conversation with Maryna Shchehelska, it becomes clear we approach Lost Sound of a Forgotten Place from different positions, and therefore arrive at different conclusions. I leave here the theoretical framework the artist operates within, as an invitation for two perspectives to coexist and interact differently with each new reading.

Drawing on memory studies, Maryna Shchehelska rejects the notion of memory and forgetting as opposites or unrelated concepts. What is forgotten can be remembered; neither forgetting nor remembering is absolute. The artist doesn’t define the carol or the village as something long gone or no longer existing. Instead, she highlights the ruptures caused by the war. In her view, the ‘museification’ and placement of the song in a ‘glass display’ already happened in 2007, when the song was recorded and released on CD. A live performance, by contrast, takes it out of the display case.

I also think about the circling that has marked the lives of people with the experience of internal displacement or exile. Over the years, with no access to their hometowns or homes, memory of a place begins to fade. Doubt grows: will anything still be there, waiting for a pilgrimage?

The construction ‘I remember’ is perhaps the only one possible at moments when return is blocked by occupation, a destroyed home, or other uncontrollable circumstances. This ‘I’, manifested in art and public discourse, allows one to find their own and empathize with others. But does such an ‘I’ exist in Lost Sound of a Forgotten Place? More importantly, who are ‘we’, and what are we gathering around?

Artist talk with Maryna Shchehelska after the presentation of her work in progress, Lost Sound of the Forgotten Place. Photo by Anastasiia Telikova, 2024.

The works of Nana Biakova and Maryna Shchehelska represent different distances and capacities for motion. In Nana Biakova’s living archive is the study of Butoh and access to objects and places in Mykolaiv. Both through personal experience and artistic practice, she consistently enacts a philosophy of motion: applying knowledge gained while traveling, seeking herself in motion and places, interacting with more-than-human agents. Maryna Shchehelska, in contrast, works with a distant context and takes the culture of the Other as her material. This approach brings challenges, especially in balancing the artist’s own intentions with the desires of the community whose heritage is being invoked. In this case, the residents of the village of Yehorivka were not involved in the process. When feedback is impossible, the place — as told through body and objects — disappears. Movement in Lost Sound of a Forgotten Place breaks off due to insufficient information about the village of Yehorivka, in other words, due to the actions of the Russian army. Colonization and the empire’s violent policies erase the traces of a place not fully mapped, neither physically nor digitally.

When we describe a place as abandoned, what future do we envision for it? Perhaps it enables archaeologists or other settlers to stake out a perimeter and begin digging. Or else, it signals a belonging to a longer journey or the possibility of return. During war, the forced displacement of people requires neither theoretical justification nor precise terminology. Ultimately, the fact of abandonment precedes the verbal frame. Still, in each case, the place continues to be inhabited by hidden motions. A brush swipes dust off a shelf, a shovel’s edge scrapes the ground. The performance is an imprint of the place, and we bear responsibility for it.

The text was written by Asia Pavlenko at the invitation of the Antonin Artaud Fellowship.

Translation — Yulia Didokha